| Case name: | Rundle v State Rail Authority of New South Wales [2002] Aust Torts Reports 81-678 |

| Legal action: | Negligence |

| Incident date: | |

| Jurisdiction: | Sydney, Australia |

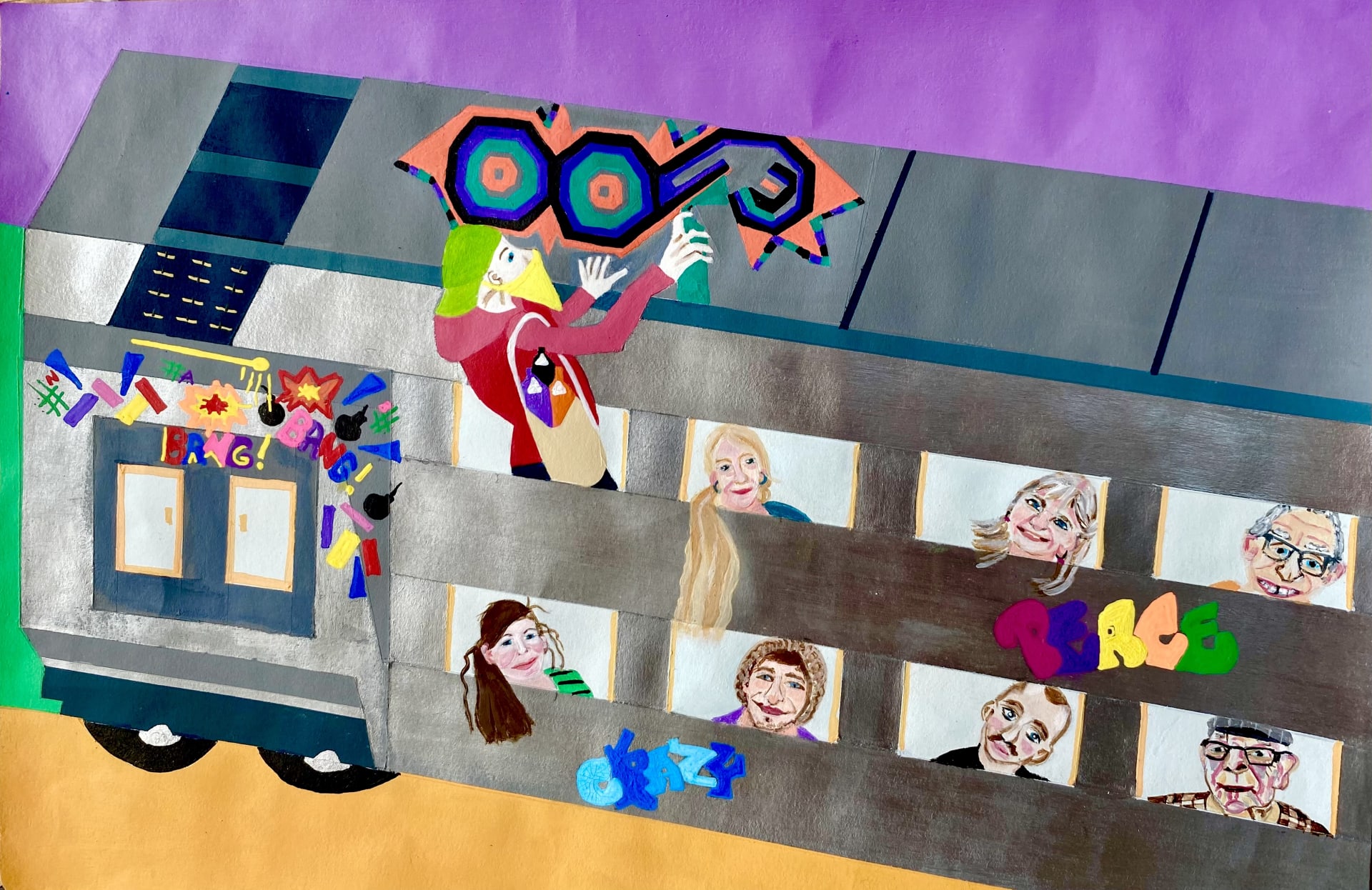

In May 1994, 15-year-old Kane Rundle was severely injured while travelling on one of the defendant’s double-decker silver train carriages. At the time of the accident, Kane was hanging out the window of the train, spraying graffiti on the roof of the carriage. This case considered the question of whether the defendant Rail Authority owed a duty of care to protect Kane from such harm.

Oops!…I did it Again: Vandalism on the Rails

Described by the New South Wales (NSW) Supreme Court as a ‘troubled child’, Kane Rundle grew up with an alcoholic father and a mother who was addicted to heroin. He regularly skipped school, used marijuana, and sprayed graffiti in public places. By the age of fifteen, he had been apprehended by authorities for his graffiti activities on three occasions. In particular, Kane enjoyed disfiguring railway property. He sprayed graffiti on trains and had in fact been doing so daily for several months before his accident. He mostly wrote one of his ‘tags’, which included the words ‘oops’ and ‘fork’.

Kane’s usual practice was to board one of the defendant’s trains at Revesby in Sydney’s South-West. He would travel two stops along the East Hills Railway Line to East Hills Station.1 During his short period on the train, he would search for an empty carriage and test the windows to see if he could find one which had its rubber gasket removed. The rubber gasket prevented the windows from being opened beyond a certain narrow width. Once he located a window without its gasket, Kane would manoeuvre the top half of his body through the window, twisting his hips so that he was effectively sitting on the outside of the carriage. This allowed him to reach up and graffiti the roof of the train.

On the date of his accident, Kane had manoeuvred himself out the window and, using a spray can, had started to write his chosen tag–‘oops’–on the train’s roof. He had written two ‘oo’s’ and part of the ‘p’ when disaster struck. As the train was travelling down the line, Kane’s head struck a fixed object beside the track—most likely a stanchion or signal—causing him severe injuries.

Kane was found lying on the floor of the carriage, bleeding from his head. His injuries caused him to have no memory of the accident and he was left with a speech deficiency and impaired balance. He also suffered a number of epileptic fits following the accident, and his left arm was rendered almost entirely useless. The accident also caused Kane to suffer a significant impairment of his intellectual and social skills. While he was able to enter into a romantic relationship and have a child in the years that followed the accident, his relationship broke down after he began suffering from delusions and brought a machete into the house. Kane was also unsuccessful in obtaining any employment following his accident.2

The Negligence Claim

Kane sued the State Rail Authority of NSW in negligence for damages for his personal injuries. In particular, he argued that the defendant had failed to prevent the windows of the train from being opened more than ten centimetres, such that they would not have allowed a person to manoeuvre their body through the opening.

Both parties agreed that the defendant owed Kane a duty of care to take reasonable steps to provide a safe railway carriage. However, there was disagreement about the scope of that duty. The defendant Rail Authority argued that its duty was to exercise care in relation to dangers likely to arise from the ordinary use of the carriage which might reasonably be expected. By contrast, Kane argued that the defendant’s duty extended to exercising care in relation to all dangers which might reasonably be expected, in light of the defendant’s knowledge of the behaviour of its passengers.3

In the Supreme Court of NSW, McClellan J found in favour of the State Rail Authority. This was not because Kane was engaged in an illegal act at the time of his injury. Indeed, it is well-accepted that a duty of care can still be owed to a person who is breaking the law.4 Rather, McClellan J found that the duty of care owed by the Rail Authority did not extend to ‘preventing a young person, intent on disfiguring the train, from deliberately squeezing through the narrow window opening’.5

His Honour noted that if a duty of care were owed, he would have assessed Kane’s damages at almost $1.14 million,6 before reducing this figure by 75% on the basis that Kane was contributorily negligent.7

Consideration was also given to whether the common law defence of volenti non fit injuria could have been relied on by the defendant. This defence applies where the plaintiff knows of the danger, fully appreciates the risk of injury, and voluntarily accepts this risk and its consequences.8 According to McClellan J, the State Rail Authority would not have been able to successfully raise this defence. Although Kane knew, in a general sense, that hanging from train windows was dangerous, and accepted the risk that he might fall from the train, he did not appreciate the specific risk of being hit by a fixed object.9

Kane appealed McClellan J’s decision that no duty of care was owed to the NSW Court of Appeal.

The Court of Appeal Decides

Heydon JA, Young CJ in Eq, and Foster AJA in the NSW Court of Appeal dismissed Kane’s appeal.

Duty of Care

It was accepted that the defendant owed a duty to take care for the safety of its passengers. However, it was held that this was a duty to provide a safe railway carriage by exercising care in relation to dangers likely to arise from the ordinary use of the carriage which might reasonably be expected.10 Although the defendant had knowledge, before Kane’s accident, that graffiti was being sprayed onto the roof of its double-decker carriages, the Court was satisfied that the defendant did not know that young people were hanging out of train windows in order to commit this act,11 and this was certainly not an ordinary use of the carriage.

In reaching its decision, the Court considered the High Court of Australia’s 1938 decision in Henwood v Municipal Tramways Trust (South Australia).12 In that case, a tram passenger leaned over the rail of a moving tram in order to vomit. He died when his head struck two steel poles. According to the High Court, although there is a duty of care owed by a carrier to its passengers to carry them safely and securely,13 there is no duty to ‘insure safety’.14 On the facts of Henwood, however, a duty of care was owed because the danger of a passenger leaning, or projecting some part of their body, out of the tram, was a danger that was likely to arise out of the ordinary use of the tram and which might reasonably be expected.15 It was the type of thing that a passenger might do ‘instinctively, or impulsively, or forgetfully, or as a result of illness or other physical condition’.16

The Court of Appeal distinguished the facts in Henwood from Kane’s situation. When Kane projected his body outside the train’s window, he did not do so instinctively, impulsively, forgetfully, or as a result of illness or other physical condition.17 Further, the danger was not ‘likely to arise out of the ordinary use of the carriage’.18 According to the Court, the defendant had taken adequate precautions against dangers that were likely to arise from the ordinary use of the carriage—for instance, passengers putting their head out the window for a better view, for air, or to relieve illness—by the provision of a window only capable of being opened 23.5 cm.19

According to the Court of Appeal, imposing a duty of care in these circumstances would also subject the defendant ‘to an intolerable burden of potential liability, and constrain their freedom of action in a gross manner’.20 The imposition of a duty of care would force the defendant Rail Authority to spend large sums of money in an attempt to stop this type of reckless conduct.21

Finally, the Court noted that it is very unusual for the law of negligence to impose a duty to protect another person from deliberately causing harm to himself or herself.22 It was observed that ‘[p]eople of full age and sound understanding must look after themselves and take responsibility for their actions’.23 While it was recognised that the law can sometimes extend to preventing people from deliberately injuring themselves, such as when they are too young to appreciate the risks of their deliberate act, or where they are of unsound mind,24 it was held that 15-year-old Kane was not too young to appreciate the danger of hanging out of a moving train.25 In fact, the danger was a key reason why he chose to engage in this activity, as it was considered ‘braver or bolder’ to place graffiti on the outside of the train, rather than the inside of the carriage.26

Three years after the Court of Appeal’s decision, there were reports of another case involving a teenage boy who was also injured while hanging out of a moving train on Sydney’s rail network.27 14-year-old Scott Preston Grant had been returning home after a day at the beach and, having noticed that a broken carriage door had been left open, leant out of the train to enjoy the wind against his face. He was badly injured when his head smashed against a sign adjacent to the railway track.28 The Court found in favour of Scott in his negligence action against the State Rail Authority and assessed his damages at $370,000, which was then reduced by 50% on the basis that he was himself 50% responsible for his injuries. The Judge rejected the defendant Rail Authority’s argument that the case was sufficiently similar to Kane Rundle’s case where it was held that no duty of care was owed. According to the Judge, in contrast to Kane’s conduct, the behaviour of Scott Preston Grant was ‘impulsive and childish’ and thus fell within the scope of the defendant’s duty of care.29

Breach of Duty

The Court of Appeal in Kane Rundle’s case further held that, even if there was an applicable duty of care, this duty was not breached by the defendant. The degree of reasonable foreseeability was at the low end of the scale and overcoming the problem with the carriage windows would be expensive and disruptive. At the time of Kane’s accident, the Sydney metropolitan railway network had 775 double-decker silver carriages in operation. It was calculated that it would take two people, working together during the night, at least a year to glue down the rubber gaskets on all of the windows. Fixing this problem would therefore either be extremely costly, or result in major disruptions to the entire Sydney train network.30

Conclusion: Foolhardy Conduct on the Rails

The Court of Appeal’s decision is one in a growing line of cases which suggest that courts are increasingly placing a higher level of personal responsibility on plaintiffs. Not only was Kane Rundle’s conduct ‘extraordinarily dangerous, reckless and foolhardy’,31 but he was, at the time of his accident, tortiously damaging the defendant’s property. As recognised by the Court of Appeal, it would ‘not conform with the elements of a tort based on reasonableness’ to hold the State Rail Authority responsible in such circumstances.32

Stay tuned for next month’s post when we will take a break from the tort of negligence and consider the equally exciting tort of defamation!

-

Opened in 1931, the East Hills Railway Line serves Sydney’s southern and south-western suburbs. ↩︎

-

Facts taken from Rundle v State Rail Authority of New South Wales [2002] Aust Torts Reports 81-678, [2]–[5] and Rundle v State Rail Authority of New South Wales [2001] NSWSC 862, [1]–[12], [40]–[64]. ↩︎

-

Rundle v State Rail Authority of New South Wales [2002] Aust Torts Reports 81-678, [34]. ↩︎

-

Rundle v State Rail Authority of New South Wales [2001] NSWSC 862, [68]–[71], citing Henwood v Municipal Tramways Trust (South Australia) (1938) 60 CLR 438. ↩︎

-

Ibid [89]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [124]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [115]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [99]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [113]. ↩︎

-

Rundle v State Rail Authority of New South Wales [2002] Aust Torts Reports 81-678, [51]–[52]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [7], [49]. ↩︎

-

(1938) 60 CLR 438. ↩︎

-

Ibid 444 (Latham CJ), 452 (Starke J), 455–6, 466 (Dixon and McTiernan JJ). ↩︎

-

Ibid 455–6, 466 (Dixon and McTiernan JJ). ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Rundle v State Rail Authority of New South Wales [2002] Aust Torts Reports 81-678, [53]. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid [56], quoting Sullivan v Moody (2001) 183 ALR 404, [42]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [56]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [57], quoting Reeves v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis [2000] 1 AC 360, 268 (Lord Hoffmann). ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid [57], quoting Reeves v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis [2000] 1 AC 360, 379–80 (Lord Hope of Craighead). ↩︎

-

Ibid [36], [58]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [42]. ↩︎

-

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Rail victim awarded $185,000’, Sydney Morning Herald (online, 4 June 2005). ↩︎

-

Facts taken from State Rail Authority of NSW v Grant [2003] NSWCA 255, [3]–[4] and Sydney Morning Herald (n 27). ↩︎

-

Sydney Morning Herald (n 27). ↩︎

-

Rundle v State Rail Authority of New South Wales [2002] Aust Torts Reports 81-678, [61]–[62]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [49]. ↩︎

-

Ibid [48]–[49]. ↩︎